Cybersecurity futures

The first annual Cantor Lecture, funded by the Vice-Chancellor of Bradford University, Brian Cantor, on similar lines to the series he had funded when he was Vice-Chancellor of York University, was given on 30 June 2015 by Prof. Sadie Creese, Professor of Cybersecurity at the Department of Computer Science, Oxford University where she has been since 2011; she was Professor and Director of e-Security at the University of Warwick’s International Digital Laboratory from 2007 and previously at QinetiQ. She is currently on a sabbatical.

She began by looking at our heritage when cybersecurity meant network and computer security and then information security and then information assurance, or confidence in the chain of information security. But once people realised that 100% security is impossible, the focus shifted to the concept of risk and how much risk we are prepared to accept.

Traditionally, a vulnerability was seen as a weakness in the system but it is better to see vulnerabilities as contained within a whole process as in the case of Stuxnet.

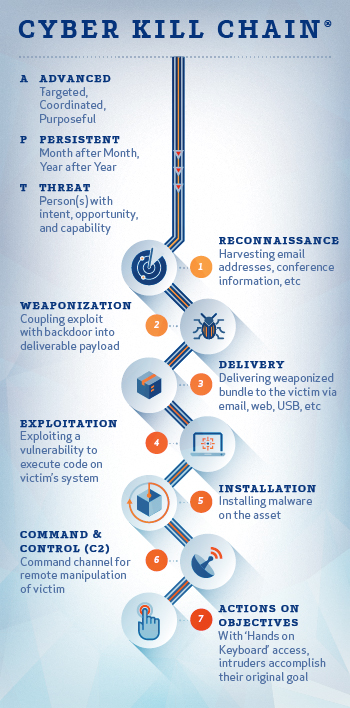

Lockheed Martin (Hutchins et al. 2010) came up with the concept of the kill chain.[ ]

]

In other words malware today normally consists of an advanced persistent threat rather than smash and grab exploits.

The problem is that it is very difficult to spot attacks because:

-

the cost of entry is a smartphone;

-

we are all now subject to insider attacks because the old strategy was to keep bad things out but we are now all insiders and most people do not know the equivalent of locking the doors to keep people out.

In addition, we are putting our digital assets where anyone can access them instead of in local storage.

Today the context of cybersecurity includes:

-

socio-technical dependency: we are becoming fully instrumentalised human beings;

-

socio-technical criticality: what we regard as our critical assets;

-

entanglement and vulnerability: we cannot protect our identity in cyberspace; it does matter how we are expressing ourselves; we are vulnerable; we are all inside the system; our online self is our real self — but online can lead to strange relationships and has become a place to recruit or coerce people;

-

international stability: we need to look at technology in the construction of acts of war and its implications for international stability.

We need to see cyberspace as an environment which we have to develop as a sustainable environment for the future. We have to forget the old controls, keeping things out like malicious files or setting standards for people on the Internet. We cannot rely on others to keep our data safe or even to advise on the best way to keep us safe and we cannot assume that we are too small. Cybercriminals are increasingly seeking smaller returns but from more small companies because staff in smaller organisations tend not to understand the risks.

Most people underestimate the risks. Part of the problem is that we cannot measure, predict, know the persistence of or insure for these risks. Another part is that people do not know:

-

how they can engage;

-

how they can be harmed;

-

how they can protect themselves.

For example, some stuff takes place at pace; some stuff takes time; some stuff is intended to create noise in one place to divert attention from another. How do we collaborate to deal with this? We have to do this because we are all insiders now and we are protecting ourselves from other people on the inside, not from outsiders.

It seems that cybersecurity will no longer simply be a technological problem but a human-technology challenge in which understanding the human component will be as important as understanding the technological.

In the succeeding question and answer session perhaps the most interesting answer was in relation to a question about people’s reluctance to give consent to the use of their data in medical research. Prof. Creese argued that the problem was the open-ended nature of the agreements that people were expected to make. She argued that people would be more likely to give their consent if the researcher had a relationship with the person and the person was able to give individual consents to specific parts of a research programme and also withdraw that consent at any time. No-one, she said, had ever offered this type of consent.